Why do my friends act like TikTokers? How algorithms have flattened individuality

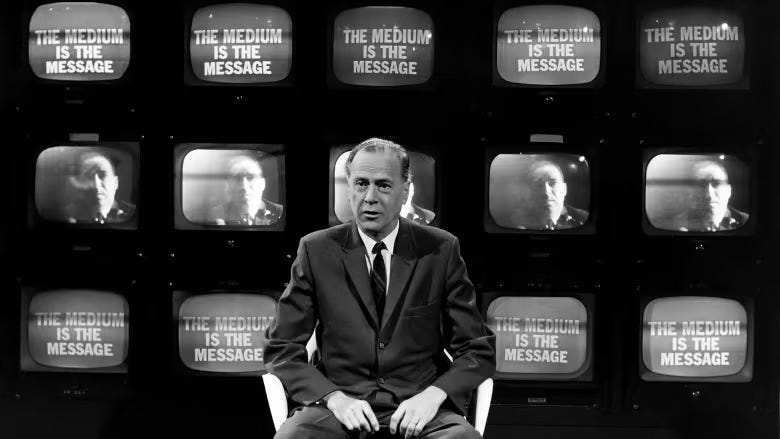

“We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us,” said media theorist Marshall McLuhan…

I swiped off TikTok and onto my group chat to open a high-angled video taken by my friend telling the story of a semi-mundane event that had just happened. What would be a verging on ignorable text has me gripped by its narration.

Much like all the content I have been consuming for the past 20 minutes on TikTok. It struck me, my friend had taken on the standard captivating manner of the generic TikTok influencer, not just in this video but in daily life too and she wasn’t the only one, I had been doing it as well. And I suspect due to our homogenizing tastes, and the democratising influence of digital culture, most teens and young women have adopted it along with.

Where we used to have relatively declarative voices it now sounds like everything we say is a question, quickly asked as a nervous school child rushing through an unsure answer. This is known as uptalk, delivering statements with a rising intonation at the end as if asking a question. This coupled with the speed at which many online influencers speak, probably because of previous time limits on videos such as TikTok’s initial fifteen-second video limit, is the voice that follows me everywhere. Both on and offline. It’s the accent of the internet, surpassing geographical borders and into real life.

The more I think about it, the more I question, why is it all 14–24-year-old girls and young women seem to sound the same, dress the same and even appear to think and act the same. Social media and algorithms have not just created a homogeneous voice but a homogeneous young woman.

I spoke to Shaniya, a 25-year-old content creator from North Carolina who makes videos essays for YouTube about contemporary digital culture. They specifically focus on the reasons behind trends and the role they take in contemporary society.

There are countless ‘internet aesthetics’, so why does it feel like everyone is the same?

“On the surface it’s great, there have never been so many sub-cultures young people can find communities in. ‘Cottagecore’ (an internet aesthetic consisting of ‘slow living’ and country life) seems miles away from the likes of Y2k, which is all for embracing the bright and tacky.

It seems like we have so much choice, but I think this assumption glazes over what's historically been at the heart of young communities. Personal struggle and local values. That’s where the similarities lie, from being on the internet it’s like one big community who feel like they face the same struggles, where there used to be geographical or occupational differences now it's mostly just generational, hence people seeming more like each other than before.”

Shaniya adds that this view is only applicable to the privileged western world where people can choose specific lifestyles and identities. “I don’t want to sound overly critical of individual homogenization, all these people who can define themselves by their ‘aesthetic’ are extremely lucky, it is a privilege to choose any kind of lifestyle. Those in places like Palestine and Congo do not have luxury to choose an identity of any kind. This is an incredibly first world problem.”

What effects do these trends have in the real world?

Over the past decade, there has been a cultural and commercial shift to get everything online. “The Internet is becoming the town square for the global village of tomorrow," said Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, furthering Marshall McLuhan’s notion of an interconnected global village. But there has been another turn too. The places and spaces we see operate only online are coming out of the URL to IRL.

Shaniya adds to this, “you can see the effects of online culture in the real world, both good and bad. I would say young people have generally become more accepting and knowledgeable about the world outside of their immediate circle. However, I think older generations assume we have no hierarchy within our cohort anymore, which is not the case. The internet ‘aesthetics’ that perform the best online are all predominantly white, skinny, rich girls. Even within communities for POC, plus size etc. leading creators in these spaces are pretty much who is at least closest to this” (white, skinny, rich girls).

What Shaniya says reinforces some recent research I have done surrounding the evolution of the specific ‘quiet luxury aesthetic’ and it’s numerous rebrands to stay relevant, such as ‘clean girl’ ‘coastal grandma’ and most recently ‘tennis-core'. Which all denote an idealised wealthy, white, leisurely lifestyle.

How autonomous is the ‘choice’ people have over these identities?

“I’ve actually been thinking about this recently” Shaniya tells me. “Obviously, I am, and have been aware of the influence the algorithmic nature of social platforms has on content consumed and therefore identity creation, but until recently I didn’t see it as a massive problem. But now, what I think could potentially be harmful is that people believe they are making autonomous decisions when in fact they are just being given the illusion of choice”

I agreed, mentioning that I used to find it useful in the algorithmic world to discover new music based on my engagement with book or fashion content.

We concur that the algorithms impact of encouraging coherent identities has constrained parts of our own identities that don't align with the cookie cutter ones prescribed on social media. Looking back a few years, I can see my identity was almost handed to me by networks such as Pinterest and TikTok already perfectly curated and coherent. However, this missed out on a lot of things that make me who I am, such as my life experiences and values. This links back to what Shaniya said originally, struggles were key to curating identity, "if you base your identity wholly off a certain ‘look’ online it will never be you, it just won't feel right” The note our interview ends on reminds me of a post I saw online when I first started questioning whether my identity was really me.

This identity is an algorithmic identity, or digital identity as it is how big tech brands have labelled you, and therefore commercialised you. The algorithm groups similar types of content and recommends it to users with comparable interests, often successfully matching tastes in one sector to another e.g. ‘You listen to Taylor Swift, maybe you would like Gilmore Girls!’.

This data is quantitative, not qualitative as it must be processed by a machine. There is no human curator looking and drawing similarities between two or more media types. It is all reduced to equations, even subjective topics of film or music taste are all translated to numbers, such as 'x number of watchers rated y film an average of z.' Then after comparing user profiles it will draw similarities between users resulting in a de facto echo chamber of cultural consumption.

While it might not be great for creativity or variety of choice, Shaniya was right. Even having the time and option to investigate online identity and therefore write this article is an incredibly privileged choice to have the autonomy to make.

However, I do see a more serious side to the algorithmic prescribed identity. When individuals with similar user activity are only shown content and others like them, it can lead to an echo chamber where they believe their way of thinking, their preferences, and their beliefs are the only right ones, as these views are constantly reinforced. This can then lead to clashes both on and offline when they encounter differing opinions.

Media scholarship has established that echo chambers are one of the surest ways to speed up the dissemination of fake news. Jon Roozenbeek, assistant professor of psychology and security specifically focusing of disinformation in digital media at Kings College London tells me, “There are generally four stages to fake news: it starts with emotion, is amplified by bots and the algorithm, leads to pitching sides against each other, and in turn makes people become active against each other.” Jon further explains this could be seen in the altercations between Palestine protestors and the far right on Armistice Day.

While this is a few steps removed from cultural echo chambers, the power of leisure-time media should not be ignored. Art and culture have a long history of intertwined propaganda, as evidenced during the First World War and the Red Scare. The homogenization of similar digital identities into a large 'super culture' can incite emotions and a sense of belonging, further fueling polarization and reinforcing beliefs among those who are algorithmically grouped together in the digital world.

Another proven harmful effect of the accepted prescribed identity is when it is one encouraging unhealthy consumption or practices, yet online they are framed in an appealing way.

Content aestheticising mental illness has long been rife on social media such as Tumblr, and more recently Pinterest and TikTok. However, now with algorithmic acceleration it can have fatal consequences.

In November 2017, 14-year-old Molly Russell from Northwest London took her own life. Her death was later described by the coroner, Andrew Walker as “an act of self-harm whilst suffering from depression and the negative effects of online content”. This was the first-time social media has been directly labelled as potentially lethal.

Algorithmic recommendations played a major role in the recommendation of depression and self-harm posts Molly was exposed to. She had assembled a Pinterest board of 469 images of these distressing themes. Wired reported that she received one email from the platform recommending, “Depression Pins you may like”, including a picture of a bloody razor. Facebook also recommended thirty different accounts that “referred to sad or depressing themes”. Walker named this a ‘binge period’ where Molly would consume the content automatically shown to her, which in this case proved deadly. Meta, parent company of Facebook and Instagram have now restricted direct searches for the terms Molly was shown, however they are still easily accessible through a specialised internet language created to avoid censorship e.g. ‘unalive’ instead of dead.

This case emphasises the machinery of algorithms. They can tell no difference between a post showing the latest interior design trends to those that encourage self-harm. They are machines made to priorities clicks and engagements over the user's well-being.

Once these digital platforms have identified you, sorted you into a specific group through data, giving you a digital identity, it is hard to escape.

As more and more of our lives move online it is harder to avoid algorithms, as usage of digital media sites have become almost a necessity of everyday adult life, such as electricity or transport links.

There is only so much an individual can do to control and regulate what they are shown online. Whether the content generalizes their cultural preferences, packaging an identity with corresponding media and interests, or exposes them to harmful content with devastating consequences. The influence of these algorithms can significantly limit the opportunity to truly know oneself, and this is the best case scenario.

Thinking back to my friend's video reminding me of a TikToker I now realise just how harmful the effects of the algorithm can be. Much harsher than just sameness of people and culture, to reduce social networks biggest flaw down to this would be a great oversight of some truly life-altering effects it is having, from polarization to mental illness.

By the end of my research for this article I feel stumped. What power do I have in comparison to this equation that is seemingly ruling the world? I worry for the children and teens of today, they will be exposed to more media and in a sense more choice than ever before, yet I think the cost might outweigh the benefits.

There has been government action resulting in the Online Safety Bill, but with the power and success of these big tech firms I'm sure they will find ways around this. The bill does not regulate the platforms holistically, only when operating in the UK. There needs to be global action that will hold firms accountable before the case of Molly Russell becomes ‘normal’.

With so much emphasis on our online personas, their real world implications and the increasing state level legislation, it does leave me wondering, in a neoliberal world that is growing to be more digital than physical, in the next ten years who will be more real, us or our algorithmic identities?

You can find out more about Molly Russell and support the charity set up in her memory, campaigning for stricter online regulations here. Feature illustration by Simone Golob.